Vision of dancing beyond the desert with dreams pays off

In the Hexi Corridor of western Gansu province, where the wind strips the earth bare of vegetation and the Gobi swallows grass, Jin Shumei once stood in the canteen of a migrant village school and asked 65 boys — most of them notorious troublemakers — to dance. The teachers had been incredulous. "These children?" they asked. But Jin, founder of Jiuquan's Little Poplar Dance School, who is also vice-chair of Gansu Federation of Literary and Art Circles and council member of China Dancers Association, insisted. She believed that in those very boys whom society had written off, the seeds of transformation might take root.

Dance was Jin's unlikely weapon in the campaign against poverty. When she began her rural education project in 2013, villagers scoffed: how could pliés and pirouettes fill empty bowls? But Jin argued that true poverty was not just economic. It was cultural, even spiritual. Left-behind children, many from divorced or migrant worker families, were dropping out of school in alarming numbers. Girls were told that dancing was "bad", boys that studying was useless. To Jin, the cycle was clear: "The poorer, the less educated; the less educated, the poorer." To break it, she turned to art.

The first rehearsals were chaos — children tumbling out of line, some brawling mid-warm-up, others feigning stomachaches. One boy tested her with a lie about needing hospital care. Jin only smiled and offered to pay his bill herself. The boy's eyes welled up. "My stomach doesn't hurt," he confessed. From that day on, he studied with a zeal that astonished his teachers, earning his first passing grades. Others followed. The "problem kids" stopped fighting, began greeting teachers politely, even turning in homework on time. Art, marveled Zhao Ruheng, then head of the China Dancers Association, "can be so subtle and effective".

Jin knew the subtlety well. She herself had entered dance late as she was already a mother when she trained at the provincial art school. Her classmates mocked her stiff limbs; her teacher called her efforts as a waste of resources. She persevered through bruises, fainting spells and ridicule until, finally, she earned grudging praise. That resilience shaped her belief that every child, however clumsy or unruly, could change through persistence and love.

Jin's vision expanded. With a team of volunteers, she carried a rural children's dance aesthetic education project to dozens of schools, traveling thousands of miles to train teachers who had never set foot in a dance class. In a few years, nearly 30,000 rural children in Gansu had danced steps she choreographed. Some even reached Beijing, where boys from Dushanzi Ethnic School performed on some higher stages, their eyes wide with wonder at skyscrapers and elevators, their feet stamping to rhythms that would later carry them onto national television.

But Jin's work was not only about the children. It was also about cultural roots. Dunhuang — the Silk Road oasis with its celestial murals of flying apsaras — has long been her spiritual home. Out of its grottoes she distilled Healthy Dunhuang Dance, a modern fusion of ancient poses and medical science. In its flowing arcs she wove tai chi, qigong, yoga even anatomy and traditional Chinese medicine. To watch the sequence "the curved three bends of a bodhisattva's form" is to see both a dance and a therapy: stretching bones, calming the mind, stimulating the lungs and intestines, staving off the sedentary ailments of modern life. Published last year as a national tutorial, Healthy Dunhuang Dance represents, in her words, "a way to cultivate both the inner and the outer self".

For Jin, the strands of her life — poverty relief, children's education and Dunhuang's cultural legacy — braid into a single philosophy. Dance is not decoration; it is nourishment. In classrooms stripped of art, she insists on beauty. In villages hollowed out by migration, she insists on dignity. In children dismissed as hopeless, she insists on possibility.

Late at night, after returning from a Hong Kong tour with students, she wept quietly at the gates of Xiaojinwan School. It was exhaustion, yes, but also triumph: she had brought them back not just safely, but changed. In the eyes of those once-restless children — now thinking of becoming teachers themselves — Jin saw her conviction turning into reality. Even the smallest movement, if practiced with care, could redirect a life's course.

- Vision of dancing beyond the desert with dreams pays off

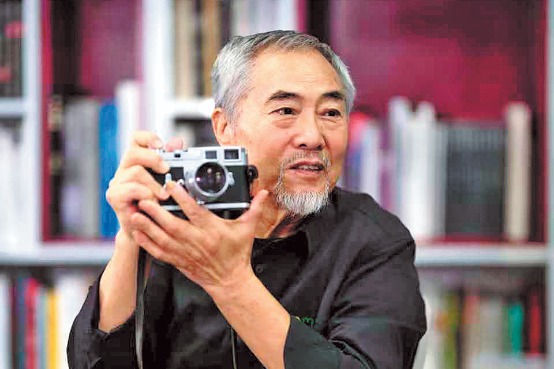

- Stories of the times and humanity told through a lens

- Chinese Generation Z youth break traditions with honest talk on death

- Breaking silence: Reconciliation with end of life

- New plan to boost fight against hepatitis

- Ancient find reveals secrets of lamp fuels