Confucianism maintains bridge between two cultures

Tradition's dual legacy

Arguing that Confucianism has historically provided both ancient Chinese and Korean societies with a "unity of purpose" and imposed "constraints", Lim believes scholars in China and South Korea should now "reexamine the tradition's dual legacy — its liberating and limiting dimensions" — to "preserve and refine the humanistic ideals that once offered moral guidance and social cohesion".

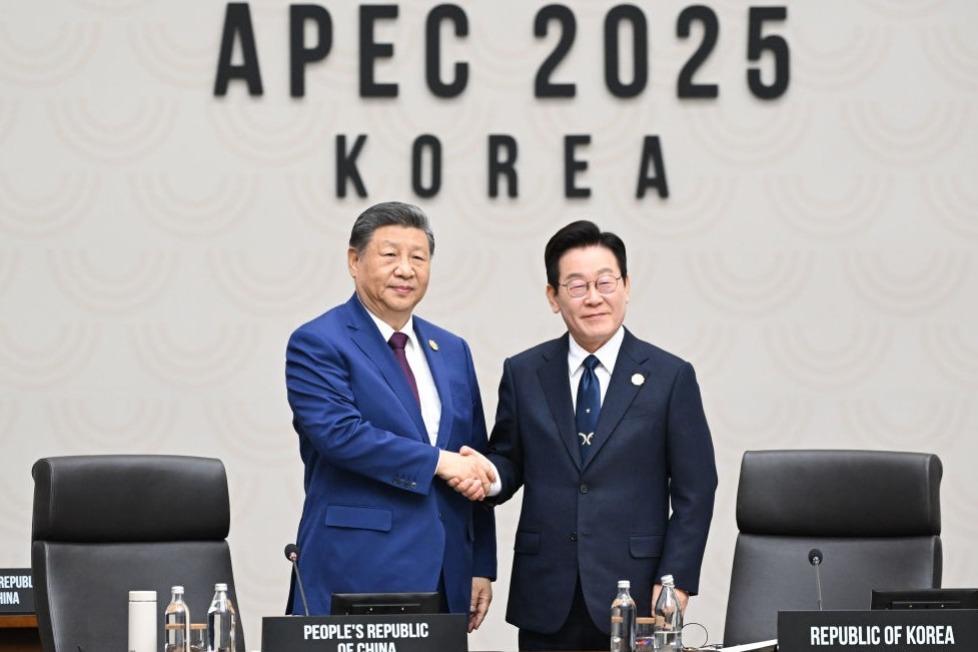

In recent years, Confucian organizations in both countries have increasingly engaged in dialogue. Chinese administrators and scholars of Confucian temples have visited South Korea to study the operations of hyanggyo — former local Confucian schools that now serve as cultural institutions and tourist sites.

Meanwhile, South Korean Confucian scholars have traveled to Qufu in Shandong province, the birthplace of Confucius, for ritual exchanges and ceremonies. This renewed interaction reflects a shared recognition of Confucianism's enduring significance and its potential to foster cross-cultural understanding across East Asia and beyond.

In 869, 12-year-old Choe arrived in China and, as Lim explains, this decision reflected Silla's rigidly hierarchical society — Choe, despite his talent, was not of royal lineage and sought to overcome social barriers by studying in China.

"A wave of Silla students was already heading to Tang," Lim notes. "In 837, 216 traveled to China. Those who had studied in Tang were considered elite, with a near-guaranteed path to official careers upon returning to Silla."

Returning home many years later, Choe encountered the same rigid social hierarchies, yet he persevered. "At that time, Silla had only recently embraced Buddhism, while Confucianism and Taoism remained largely unfamiliar. Drawing selectively from China's diverse philosophical traditions, Choe developed ideas compatible with Silla customs and articulated a coherent intellectual system for his homeland. Remarkably, he synthesized Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism — sometimes mutually critical — into a unified framework, an accomplishment made possible precisely because he was not born into any of these traditions, but encountered them as an outsider studying in China," Lim says.

Before he left for China, his father gave Choe a stern warning: If he did not pass the imperial examination within 10 years, he would cease to be his son. Choe accomplished that goal and went far beyond it, emerging as both a Confucian sage and a literary master of classical Chinese, whose talents earned recognition across borders.

In 884, 27-year-old Choe finally bade farewell to his adopted home with a poem.

"My eyes sweep the endless mist and tide. At dawn, where crows take wing, my home I spied," he wrote.

"Years spent afar have streaked my temples white. Yet, the journey back begins to smooth my care."

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn